DOI: 10.1038/s41565-024-01676-4

Cancer Killing Nanobots

- Written by Kiara Fabbri Former Tech News Writer

- Fact-Checked by Justyn Newman Former Lead Cybersecurity Editor

This July, researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden published a study detailing their development of nanorobots that can selectively kill cancer cells in mice, resulting in a 70% reduction in tumor size. These nanorobots activate their lethal mechanism only in the tumor-specific environment, greatly improving the precision of cancer treatments.

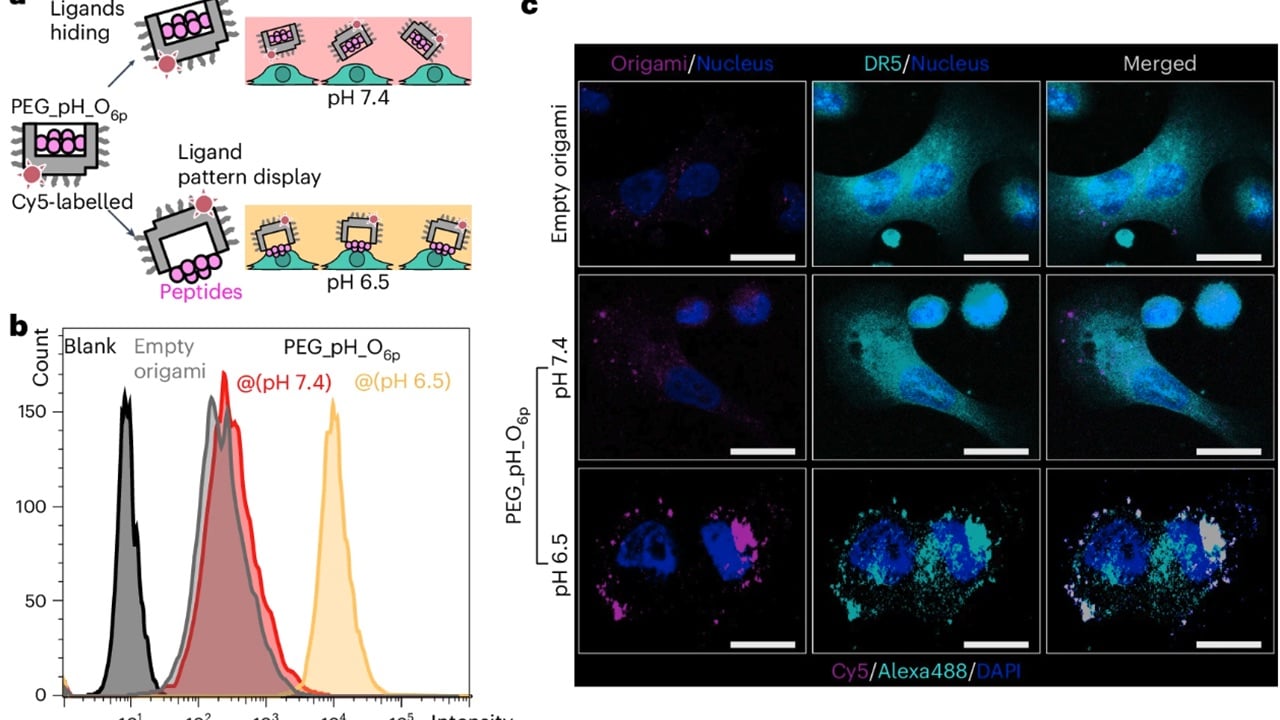

Building on their previous work with cell death triggers, researchers at Karolinska Institutet have developed a new weapon: a hexagonal structure made of six peptides (amino acid chains). Professor Björn Högberg, who led the study, explains , “If you were to administer it as a drug, it would indiscriminately start killing cells in the body, which would not be good. To get around this problem, we have hidden the weapon inside a nanostructure built from DNA.”

For years, Professor Björn Högberg’s team has been pioneering a technique called DNA origami, where DNA strands are folded into specific shapes. Now, they’ve harnessed this technique to create a microscopic “kill switch” that only activates in the right environment.

Tumors have a lower pH, meaning they’re more acidic than healthy tissue. The researchers cleverly hid the peptide weapon within the DNA origami structure. This ensures it stays inactive at a normal pH of 7.4. But when injected near a tumor, the acidic environment (around pH 6.5) triggers the DNA origami to release the weapon, specifically targeting and killing cancer cells.

The researchers tested this by Injecting the nanorobots into mice with breast cancer tumors. The results were very promising. Tumor growth was reduced by a significant 70% compared to mice receiving an inactive version.

However, the researchers at Karolinska Institutet acknowledge the need for further investigation. Lead researcher Yang Wang highlights two key areas: testing the nanorobots in more complex cancer models that better mimic human disease and evaluating potential side effects before human trials can begin.

This study brings promising news, especially for breast cancer, the second leading cause of cancer death in women . Nevertheless, further research is needed on safety and effectiveness before human trials. This targeted approach has the potential to revolutionize cancer treatment.

Photo by Lara Jameson from Pexels

New Prosthetic Interface Lets Amputees Control Limbs with Their Minds

- Written by Kiara Fabbri Former Tech News Writer

- Fact-Checked by Justyn Newman Former Lead Cybersecurity Editor

Researchers from MIT and Brigham and Women’s Hospital have developed a revolutionary prosthetic limb that allows users to achieve a natural walking gait through full neural control. This groundbreaking innovation offers amputees improved mobility and proprioceptive feedback.

MIT’s study, published in Nature Medicine, involved seven patients who underwent a surgical procedure called the agonist-antagonist myoneural interface (AMI). Traditional prosthetic limbs rely on robotic sensors and predefined gait algorithms, often resulting in unnatural movements and limited control. The AMI procedure , however, connects the two ends of amputated muscles, preserving their natural interactions and providing proprioceptive feedback. This feedback allows the brain to sense the limb’s position in space, significantly enhancing movement control.

“This is the first prosthetic study in history that shows a leg prosthesis under full neural modulation” says Hugh Herr , a co-director of the K. Lisa Yang Center for Bionics at MIT and senior author of the study. “No one has been able to show this level of brain control that produces a natural gait, where the human’s nervous system is controlling the movement, not a robotic control algorithm.”

In various tests, including navigating slopes and stairs, AMI patients demonstrated superior performance compared to those with conventional amputations. The sensory feedback, although less than 20% of what non-amputees receive, was sufficient to restore significant neural control, enabling users to adapt their gait in real-time.

AMI surgery offers several benefits beyond a natural gait. Patients who received the surgery also reported less pain and muscle atrophy. This advancement points to a future where prosthetic limbs are seamlessly integrated with the user’s body, providing a more natural and intuitive experience. Herr explained: “The approach we’re taking is trying to comprehensively connect the brain of the human to the electromechanics.” While further research is needed, this groundbreaking surgery offers hope for amputees. The ability to walk and move with a more intuitive connection to their prosthetic limb, rather than relying solely on robotic controls, represents a significant step towards a future where amputees can experience a new level of freedom in their daily lives.